COP27's Loss and Damage Fund looks to make up for failure of COP15's climate finance pledge.

A few days ago, Mustard Insights published an article about how Africa is one of the lowest carbon emitting regions in the world. Yet, the region has some of the highest at-risk regions when it comes to the effects of climate change. The African Development Bank Group (AFDB) has stated that Africa faces “exponential collateral damage”. From droughts in Eastern Africa to floods in the West, its countries have their infrastructure, public health, food and water systems, and economies under threat.

All of these may be why nearly all African countries were signatories to the Paris Agreement, pledging to make their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). However, seeing as most African countries are low- to lower middle-income countries, the AFDB estimated that African countries will need external investments of up to US$3 trillion to implement the agreed-upon NDCs. This statement was made at the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s (UNFCCC) COP25 summit held in 2019 at Madrid. This is where the issue of climate justice comes in.

The richer countries in the world tend to be the highest-emitting; hence they are the major contributors to the climate change problem. This then brings about the concept of “climate justice”: basically, it is fair that the countries which are the lowest-emitting will be the ones who have to bear the brunt of the issue? These countries, which are often low-income countries, will have the economies decimated by the effects of climate change and will have their people impoverished even further.

The $100 billion pledge

The activists for climate justice demand that these countries be the stakeholders to foot that $3 trillion bill. But the world’s wealthier countries are already aware of this, and have been for a while now. At the 15th COP, held in Copenhagen in 2009, developed countries made a collective pledge to raise USD 100 billion per year for climate mitigation strategies in developing countries.

There’s a reason the Copenhagen pledge was such a landmark event. It was seen at the time as a symbolic gesture of co-operation, an admission by the world’s wealthiest akin to “we caused this problem, and we will carry the load to solve or at least ameliorate it”. It was, as the director of the International Centre for Climate Change and Development, Salameel Huq, told Nature.com a sign of “good faith”.

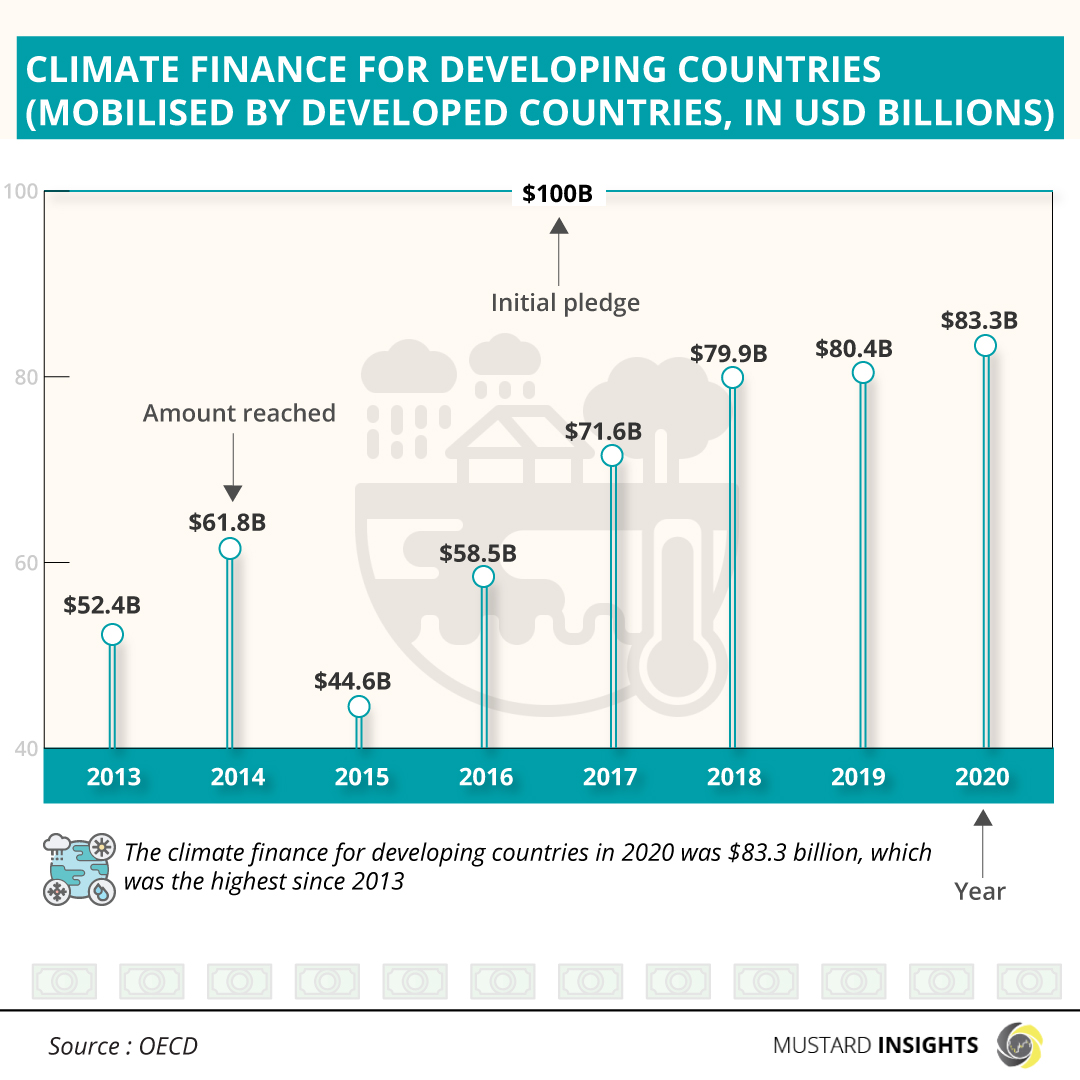

However, climate finance has not reached the US$100 billion-per-year mark in any year since the pledge was made. The data presented by Mustard Insights was culled from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), an intergovernmental body which is made up of mostly developed and wealthy nations. OECD gets it figures from national reports and there have been reports that the public figures may be inflated. Some developed countries have counted development aid and road construction financing as part of their climate funding.

Some countries such as the United States, Australia, and Canada have contributed significantly less than their fair share. Country share can be estimated based on emissions, population, or wealth. Also, A lot of the financing has come in form of equity financing and loans instead of grants, which in turn leads to the question of what exactly the funding has gone towards.

Breaking down the climate finance allocation

Climate control measures are often categorized as being either adaptation or mitigation, with some measure managing to cut across both. Adaptation measures, as the name imply, serve to help affected countries deal with the effects of climate change. This financing is most likely to come in form of grants. Mitigation projects are often new projects such as solar farms, electric cars, or hydropower facilities. The bulk of climate financing have come in form of bilateral finance (one country sending money to another either as a loan or grant), multilateral finance (funds from development banks such as the World Bank, the European Investment Bank, or the International Monetary Fund), and private finance.

The bulk of the latter two have come in form of loans or equity financing in mitigation projects, seeing as these are projects that can provide a return on investment or generate profit. The OECD data shows that the bulk of climate financing have gone into mitigation projects instead of adaptation. This means that the displaced residents of a flooded village are less likely to get finance than the company building a solar farm.

Research by Julie Bos and Joe Thwaites of the World Resources Institute (WRI) estimate that countries such as Germany, Japan, and France have given significantly more loans than grants. One thing is clear: there is no magnanimity here; climate financing is nothing more than an investment opportunity. In line with this, it will not surprise the reader to know that most of the finance has gone to middle-income countries, not the poorest and often most critically-affected countries. After all, there are lesser chances for that return on investment there.

COP27 and the Loss-and-Damage Pledge

At the recently-concluded COP27, held in Egpyt at Sharm el-Sheikh, the UNFCCC reached an agreement for a “loss and damage” fund. As the name implies, this is funding entirely targeted at countries which have been hit by climate disasters. Basically, funding targeted entirely at adaptation measures. This funding will cover both financing and technical assistance to developing countries.

It’s easy to scoff at this development; this writer initially did. Like the British comedian and political satirist, Marcus Brigstocke, once said: “The delegates sat, and the delegates talked...and agreed to come back again the next year”. However, two things give hope that this is unlike the other.

The first is that there seem to be an understanding that adaptation measures are of a greater importance than mitigation at this present moment. 2022 saw countries like Nigeria, Indonesia, and Pakistan ravaged by floods; Madagascar, Ethiopia, Somalia, and Kenya saw severe drought; too many countries to name are experiencing food insecurities as weather abnormalities have led to harvest failures. This is the primary issue at hand.

Secondly, the United Nations’ Sharm el-Sheikh Implementation Plan produced from the conference acknowledged the fact that climate financing was pushing affected developing countries into greater debt burden. Thus, the COP27 chairman, Sameh Shoukry, Implementation Plan called for the transformation of financial system and a move to a global low-carbon economy, a move which the UN estimates will cost US$4-6 trillion per year up to 2050. This will involve all from governments and central banks to commercial banks and institutional investors. This is key: climate financing can’t be seen primarily as a route to profit or an investment vehicle.

One cannot be too optimistic, but then again, one cannot lose hope either. Africa sorely needs the finance. More people are displaced everywhere, its countries are in debt, its infrastructure is crumbling, its crops are failing, and livestock are dying. Maybe, just maybe, this might be that ray of light.

Comments

Thoughts?

We won't share your email address. All fields are required.

David

2 years agoI don’t think most countries across the world are seeing the seriousness of climate change. Especially developing countries. There isn’t much education into this issue. It’s sad because the flood that happened recently has occurred before and definitely might happen again if the appropriate measures are not put in place.