- Published: 12th Dec, 2022

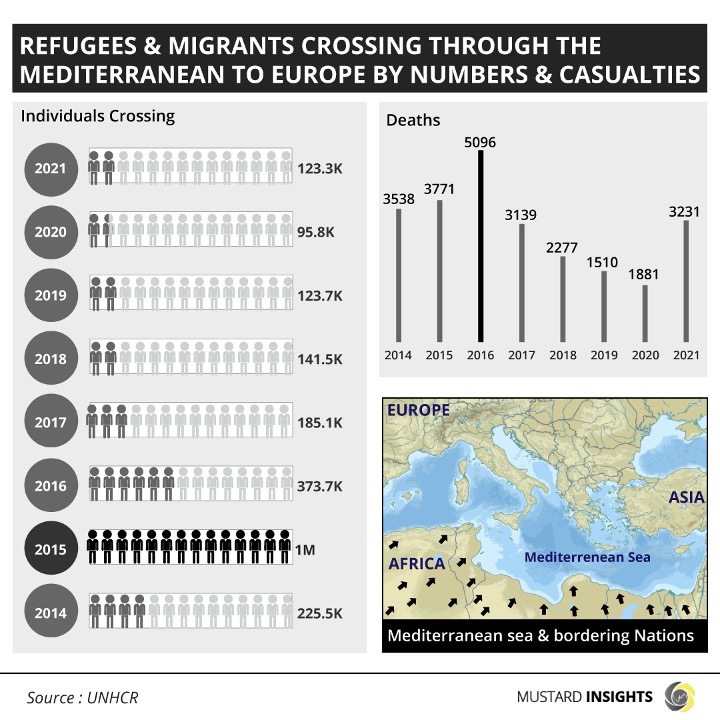

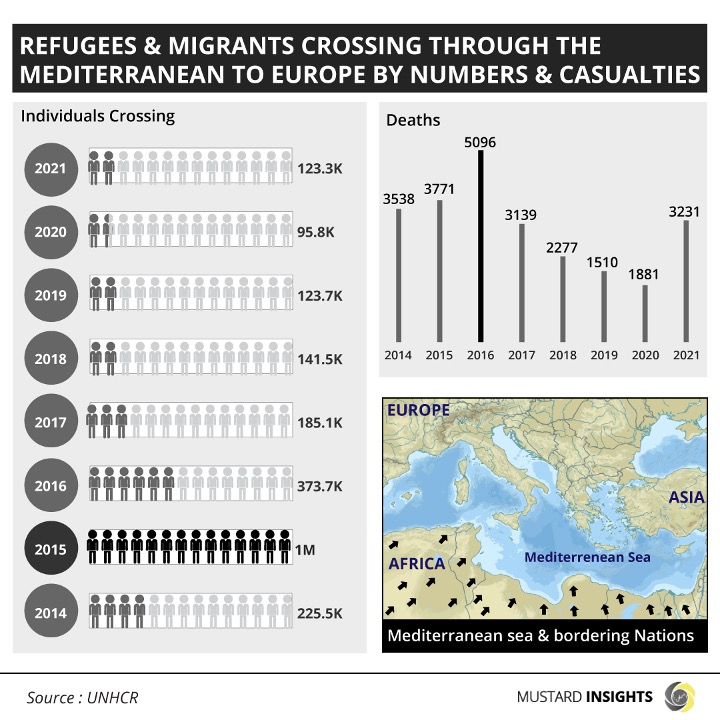

From 2014 to 2021, about 2.3 million migrants arrived in Europe through the treacherous Mediterranean Sea crossing; over 24,400 people died or went missing attempting the crossing. This is according to data from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the United Nation’s de facto refugee agency. The agency admits that this numbers are most likely far below the actual figures, as most deaths go unreported. It is routine for the number of missing persons to far exceed the number of confirmed deaths.

The journey from Africa to Europe via the old sea is long and filled with dangers. Refugees from both the East and West of Africa often have to endure a grueling land trek through the Sahara Desert, which stretches right across the north of the continent from the Red Sea in the east to the Atlantic Ocean in the west. It is impossible to reach Europe without crossing the Sahara and the Mediterranean, but there are different paths. Let us attempt to trace these pathways.

Travel Routes

From West Africa, the route is often through the Niger Republic and Libya. Migrants will often arrive at the Nigerien city of Agadez, where they are then put on vehicles to cross the Great Desert to Libya. According to the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), it is not uncommon for this to be a part of the journey where migrants go missing. Vehicle breakdowns are common, and smugglers often abandon migrants.

Vehicles may break down; the smugglers may get lost (the Sahara is known to be situational confusing and throw travelers off); or the smugglers may abandon migrants when they sense military patrols or checkpoints. It is also common for smugglers to also demand more money mid-crossing, and maroon those who cannot or will not meet those demands.

Migrants will then have to cross the desert on foot, and it is during this trek that a lot of migrants perish. There is the danger of dehydration, and due to this some migrants will opt for nighttime treks to avoid the searing day heat. But the night is dangerous. Travelers may lose their paths or have adverse encounters with the wrong people; in June 2022, the Nigerien army found ten migrants buried in shallow graves near the northeastern Nigerien city of Dirkou.

From the East, refugees and migrants from countries such as Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia, and Ethiopia all go through Sudan, moving to the towns of Gedaref or Kassala before departing for the Sudanese city of Khartoum, which serves as a confluence point similar to Agadez. It is from Khartoum that the most dangerous parts of the journey begin: the Sahara crossing to the north of Libya.

Smugglers at the northern Sudanese towns of Dongola and Al Dabba receive migrant to move across the Eastern Sahara. This journey, just like that in the Western Sahara, is entirely dependent on the smugglers for the same reasons like the western journey; the migrants simply can’t find their way across the Sahara on their own.

Both groups will then converge at Libya, where migrants use smuggler boats to depart northern Libyan towns bound for Italy, Malta, and Greece. Some depart from Egypt and Tunisia.

Why People Flee

It is evident that some migrants head to Europe in pursuit of better economic opportunities, especially from the West African countries like Ghana and Nigeria. However, most migrants from the East and the Horn of Africa, and even some from Central African countries like Chad, are fleeing conflict, violence, or increasingly, climate-related crises. There is also persecution with inter-tribal violence or civil wars.

Years of conflict in Eastern African countries like Somalia, Kenya, Sudan, Ethiopia, South Sudan, and Eritrea have forced many to look to Europe. As of 2021, Ethiopia had 3,954,760 internally displaced persons (IDPs), according to the UNHCR. Sudan had 2,552,174, with Somalia and South Sudan possessing 2,967,500 and 1,710,966 respectively. The UNHCR reports that there are 2,277,919 refugees in South Sudan; 805,874 in Sudan; 790,022 in Somalia; 492,465 in Eritrea, and 145,125 in Ethiopia.

Conditions in refugee and IDP camps are often deplorable. Food is scarce, as are other basic amenities; large numbers in tight spaces create unsanitary conditions and disease is rife, and there are often reports of abuse. Refugees and IDPs may stay stuck in these camps for years. As a result, most migrants will attempt the crossings, often fully aware of the horrors that may await them.

Dangers Migrants Face

Apart from the dangers stated previously, a lot of human rights abuses happen along the way. Physical and sexual abuse is common, and migrants often face extreme hunger, dehydration, disease, and a lack of medical care. Apart from migrants being abandoned by traffickers, there are accounts of kidnappings, re-routing, extortion, physical beatings, and sexual assault. Migrants who survive all of this then have to endure crossing the rough Mediterranean Sea on what are often small and dangerous boats. Thousands die or go missing in capsized boats, sometimes within the view of European shores.

The bulk of these incidents have been reported to happen in detention centres in Libya, although migrants have also reported major widespread abuses along the land routes through the Sahara. In Libya, migrants are most likely to detained by traffickers who will hike prices for the Mediterranean crossing, reneging on previous agreements. Migrants may be forced into slave labour or sold off, and gender-based violence like rapes are common. Some migrants spend as much as two years in Libya, and travelers intercepted by European coast guards or border police are often returned to Libya.

Mitigating Risks

The United Nations is working towards protecting the rights of refugees. There is an understanding that ending the refugee crisis in finality would entail ending the causes of displacement. Therefore, the UNHCR is looking to provide a level of safety and risk mitigation on migration routes and destinations.

The agency is working with the IOM to combat the issue of human trafficking; with UNICEF, IOM, and the National Council for Childhood and Motherhood (NCCM) on protecting children, and with Emergency Transit Mechanisms (ETM) to resettle migrants stuck in Libya in countries such as Niger and Rwanda. The UNHCR has also reached out to the European Union to protect those who are at sea. In this issue lies a real quandary, as most EU nations are not very welcoming of migrants.

The UNHCR has called on increased humanitarian assistance and support from all countries along the land and sea routes used by migrants and refugees. It has urged them to provide safe alternative passages and to ensure that migrants and refugees are disembarked at points where lives and human rights are prioritized and protected.