- Published: 4th Dec, 2022

In the past few days, Mustard Insights has done a deep dive into the transformation of Africa’s food systems. We did this because we have observed and fully understand the issues of food insecurity plaguing the continent. We also believe that this is not an issue that will go away organically; there has to be a careful and intentional process. This process is addressed at length in the Alliance for a Green Revolution’s (AGRA) 2022 Africa Agriculture Status Report: Accelerating African Food Systems Transformation.

The report is extensive and wide-ranging, containing research on agricultural megatrends, leadership, and sustainability. We at Mustard Insights have chosen to focus on mobilization of the financial resources needed to execute this transformation. In a previous article, we looked into the demand-side of food systems financing, with cursory mentions of the sources. Here, we would look deeper into the supply-side, the investment stakeholders.

The Public Sector

AGRA is clear that most of the investment that will be required to transform food systems will come from the private sector, with the ratio of public sector to private sector spending being as high as 1-to-3. However, public sector spending is crucial, especially in the beginning stages because it serves to create an enabling environment. Historically, governments have often driven sectoral progress by providing initial funding for technology, infrastructure, and research and development, all of which then provide a proof-of-concept to spur private sector investment.

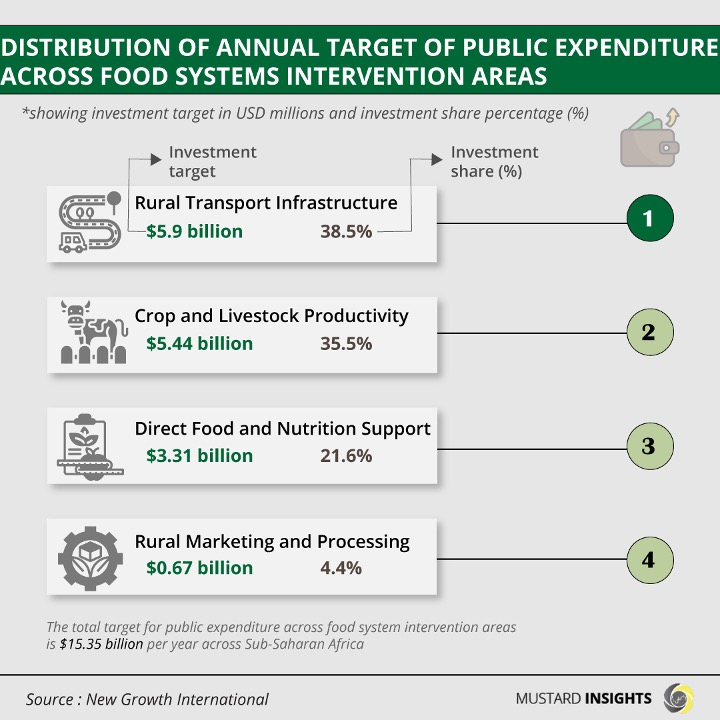

In terms of agriculture, government spending will put in place infrastructure like irrigation, warehousing, and irrigation. New Growth International researchers, Steven Were Omamo and Alexander Mills have pinpointed four major areas of public sector investment: i) crop and livestock productivity; ii) rural transport infrastructure; iii) marketing, processing and services; and iv) direct food support. Additionally, public sector investment often drives R&D and the dissemination of technology through agri-SMEs to smallholder farmers.

Private Sector Investment

Development finance institutions

DFIs can provide multilateral finance through concessional funding – loans below market rate – to countries along with technical support. Organizations such as the International Fund for Agriculture Development (IFAD) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) can provide loans and grants such as the recent awarding of a US$27.9 million grant to Ghana by the AfDB’s Africa Development Fund for the Savannah Agriculture Value Chain Development Project (SADP). DFIs can also provide catalytic funding similar to that of the public sector, especially targeted at agri-SMEs, which mt struggle to repay market value loans from other private sector investment sources such as commercial banks.

Commercial banks

The nature of commercial bank investments – often high interest rate loans, the expectations to high returns – are not usually ideal for agriculture projects, which may be perceived as high risk with modest returns. This might be why lending to agriculture from commercial banks represents just about 6 percent of their total lending. Agri-SMEs in particular could do with more commercial bank funding.

Agricultural development banks

These are Public Development Banks (PDBs) specifically targeted at agriculture. These banks can play an important role as middlemen in the value chain as they often have the ability to access longer-term loans from other large financial institutions and provide these at lower rates to players like agri-SMEs and even smallholder farmers.

Donor financing

This is an essential source of funding in most African countries, where loan defaulting can be a rather frequent occurrence. Donor financing can come from bilateral sources such as individual countries or bodies such as the G7 – Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States – which have made similar pledges in the case of climate finance. Donor financing often comes in form of emergency aid or assistance. However, it is imperative that this funding is more pre-emptive, targeting catalytic change at the national level, with money going into technology or research grants.

Microfinance institutions

These have become established in the last decade as vital sources of SME funding in Africa. They are often the route to obtaining small loans and hazard insurance. They may not have the expertise to structure agriculture-specific loans; however, this can be taught by larger-scale PDBs and multilateral organizations. Their main benefactors are smallholder farmers and agri-SMEs.

Cooperatives

These helps producers get better yields when they pool their resources together to support single struggling members or access land acquisition or capacity-building initiatives. These are particularly essential to smallholder farmers, who may be unable to access funding individually.

Institutional investors

Money management bodies such as pension funds, hedge funds, and venture capital firms presently hold as much as USS1.9 trillion in assets across Sub-Saharan Africa. However, very little of these will be invested in region’s development goals. These funds will often be invested in securities instead of sustainable development goals.

Insurance firms

Agriculture insurance is vital especially in these times. It is not unusual to hear of crop and harvest failures along with other risks along the agriculture value chain. However, very few smallholder farmers, who are the group who tend to need it the most, have access to insurance. Also, few insurance firms have products targeting agri-SMEs.

More innovative financing mechanisms

Blended finance

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines this as the “strategic use of development finance for the mobilization of additional finance towards sustainable development in developing countries”. This will often combine finance from both public and private sector bodies towards a single goal. It can come through concessional capital, grants, insurance, or technical assistance. DFIs can use this to incentivize private sector funding, as something of a DFI cooperative.

Partial credit guarantees/Risk-sharing facilities

Credit guarantees are usually targeted at addressing the previously-mentioned concerns commercial banks may have towards risky financing. They do this by diversifying or transferring agri-SME risk and reducing collateral requirements, thus allowing SMEs with insufficient collateral to access lending. They can also help commercial banks develop an understanding of the sector and guide them in structuring agriculture-specific loans.

Risk-sharing facilities work similarly, but this time the service is provided by governments by ‘de-risking’ agricultural financing. An example is the Nigerian government’s Nigeria Incentive-based Risk Sharing System for Agricultural Lending (NIRSAL).

Crop receipts

This is a system particularly targeted at pre-harvest financing. Most access to finance will often demand proof of an already-existing structure. Crop receipts, developed in Brazil in the 1990s, are critical in allowing new farmers to access facilities such as seeds and equipment on a large scale and enable smallholder farmers to mobilize the necessary funding for entry or consolidation in the sector. They also facilitate the entry of new financiers as this is a low-risk investment.

Takeaway

The above list is non-exhaustive and definitely not finalized; more innovative mechanisms will sprout up and should be encouraged, along with the reformatting of existent routes to finance. Mechanisms such as agricultural lease financing for land acquisition and warehousing receipts for storage will become mainstay as they move from first-of-a-kind to becoming recognized parts of agriculture funding infrastructure. The financial technology (fintech) industry will also play a role in digitizing agriculture value chains through mobile payments and direct business-to-customer access. More research should be encouraged, as protecting food systems is integral to sustaining life and growing communities across Sub-Saharan Africa.